The Meaning of Self-Organization in the digital age

Self-organization is a term that is supposed to work miracles in today’s economy. We want to check that carefully. The starting situation looks like this: Surely digitization is to blame for the loss of numerous jobs and the disappearance of entire economic sectors. But conversely, it creates new professions and changes structures and roles in entire sectors and in particular inside organizations. In short: it turns our world upside down. Granted, digitization is not at work alone. Gender issues, diversity, equality between minorities, migration to cities, globalization, climate change , and the universal pursuit of sustainability are other trends our societies are facing nowadays. What’s more, such trends require organizations to constantly adapt to new situations and to ensure their future through innovations. This includes certain skills that stand out from organizational and management structures and should be supported by a suitable culture. In this regard, agility is the most mentioned skill. But the central question at this point is: Can all organizations be agile enough, and if so, at what price? Science has a global answer to this: self-organization should fix it.

1. But What is Meant by Self-Organization?

1.1 Self-organisation is always présent, right?

The theory of self-organization originally came from the natural sciences; it was adapted from the social sciences in the 1960s and from the economic sciences in the 1970s. According to Wolf (2011), ‘Self-organization is one of the most popular organizational, management and corporate leadership theories of all’. Interestingly, however, the concept of self-organization does not correspond to a new form of organization from an economic, legal, or structural point of view. It is more of a ‘modern variant of systems theory,’ says Wolf. ‘Ultimately, it is about the question of whether and to what extent (sub-) systems have to be steered from the outside or from their top and whether it is not better to use the creative forces in the (sub-) systems themselves to trust’ (Wolf, 2011). As a result, every organization is a system that contains self-organizing elements;. that is, self-organization is part of every organization Due to the ‘self-referencing’ characteristic of systems, other authors postulate that it could not be otherwise.

From a social systems point of view, the manager is herself part of the system she tries to manage. Thus, ‘management is self-management of a system’ (Krohn & Küppers, 1991). In this regard, Ulrich (1985) postulates that the organization basically understands itself on the basis of its informal structures, whereby it continuously adapts and reconstructs itself based on its self-organizing abilities. The planning represents at most a necessary addition or correction of the informal structures. Accordingly, it is clear that the problem of organization is to strengthen the human characteristics for self-organization through the foresighted sketching of structures that promote economic activity at the same time. Every organization, therefore, consists of a formal and an informal part. With regard to the performance potential of corporates, the question also arises as to how these two parts can ideally balance each other.

And what does self-organisation have to do with agility?

The self-organization theory focuses on the fact that order is the result of autonomous processes, in contrast to the classic organizational idea that wants to control systems with the help of a set of specified regulations. Organization appears as an order generated by the system itself. In the social sciences, however, this is a central aspect that contradicts the Darwinian model, according to which ‘the systems in the evolutionary process are victims of their environment and largely develop in accordance with it. It is much more assumed that changes are influenced by the systems themselves’ (Wolf, 2011).

The idea of self-organization is not just the statement that every organization has self-design mechanisms. Rather, it should ‘be promoted in a targeted and conscious manner by expanding the scope for action and decision-making of the organizational members, especially those of the lower hierarchical levels’ (Bea & Göbel, 2019). This results in greater flexibility, accelerated processes, and better utilization of human resources.

With regard to human resources, self-organization is based on two assumptions. These are, on the one hand, the limited rationality of people, and on the other hand, their self-interest. The limited rationality of man, according to which his ‘ability to think, judge and solve problems’ is limited, leads to the principle of ‘knowledge of all instead of the omniscience of some.’ The term ‘self-interest’ is not to be equated with ‘egoism’ here but rather with the motivation that stands in the background of people’s actions. In practice, these assumptions lead to the following application:

The two building blocks that enable self-organization are the process structure and the group structure. With the process organization, larger, coherent complexes of tasks are created, which can then be transferred to groups that process these tasks more or less autonomously. Ideally, the group members can decide for themselves concerning the division of labor, workflow, and working hours (Förster & Wendler, 2012).

1.3 The building blocks of agility

Thus, the authors name two characteristics of an agile environment, namely, the process orientation and the autonomy of groups. But is just that what is meant by ‘agility’? In fact, there are many definitions and interpretations of this term in use. ‘The understanding of agility in practice is particularly divergent,’ says Adam (2020). The author, who based her research project called ‘Certification of Agile Processes’ on both literature research and ‘in-depth interviews with representatives of companies from various industries,’ states: The definition of agility ranged from individual terms such as ‘self-control’ and ‘flexible reaction to changes’ and the general ‘handling of the unplanned’ up to concrete tools, for example, ‘Agility is the transition to Scrum.’

Indeed, flexibility is a term that is often mentioned in the same breath as agility. Agility and flexibility were compared in a comprehensive literature review. The analysis showed in summary that flexibility is the property of a system to be prepared for foreseeable changes within defined limits. Conversely, agility is defined by the ability of the system to adapt even in the event of unforeseeable changes.

Bea and Göbel (2019) use an interesting metaphor to illustrate the agility of self-organization in comparison to an external organization. For external organizations, the path to self-organization corresponds to the transition from a palace to a tent organization. Characteristics of a tent organization are small, autonomous units; multiple qualifications of the members; overlapping tasks; unstable distribution of roles and status; open, controversial communication; flexibility; creativity; initiative; and participatory leadership. One hopes that the restructuring will also bring about a change in thinking.

2. The Path from a Palace to a Tent Organization

2.1 After all, it’s all about people

John Kotter (2019), the well-known professor from the Harvard Business School, sees management and leadership as bottlenecks on the way to agility and sends a message that is appropriate to the above-mentioned practical example. Kotter is working on a concept that will facilitate people’s reflection and the way they appear in meetings, and how they communicate. This should avoid the contradiction consisting in asking employees to change things while putting them in a non-change mental mode at the same time. Authenticity is required here, especially in communication. However, for many of the people affected, a transformation is an emotionally charged matter that can take years. ‘Change is about changing people, not organizations’, quoted Deitinger (2011). The topics of communication, emotionality, and authenticity play a central role in this context.

2.2 Ambidextrous instead of “agility versus hierarchy”

Due to the fact that agility is praised as a universal solution, one could come to the conclusion that hierarchies and managers should be abolished immediately and everywhere. The question is whether a hierarchically organized company run by strict regulations is doomed to fail. It is not so. First, hierarchies are necessary. ‘Hierarchies are effective means of increasing efficiency. This alone shows the fact that hierarchical organizational structures in the industrialized world have been established and developed over decades’ (Duwe, 2020). Second, ‘Agility is neither the miracle solution to all problems with guaranteed future viability nor the sheer chaos of unplanned hustle and bustle. Rather, it can be seen as an important addition to the process and project-related forms of organization that have dominated so far’ (Adam, 2020, p. VIII). The belief that self-organizing forms of design have universal validity is out of place. The question arises as to when and to what extent the concept of self-organization should be implemented. The literature does not provide a clear answer to this. It’s actually not a question of either hierarchy or agility, but a combination of both. In relation to such a combination, a specific term is used in the literature: ambidexterity. Ortmann (2020) writes in this regard: ‘For the tension between the rigidity of hierarchy and the requirement of adaptability, flexibility, and agility, the idea of ambidexterity can be made fruitful—two-handedness—instead of agility versus hierarchy’.

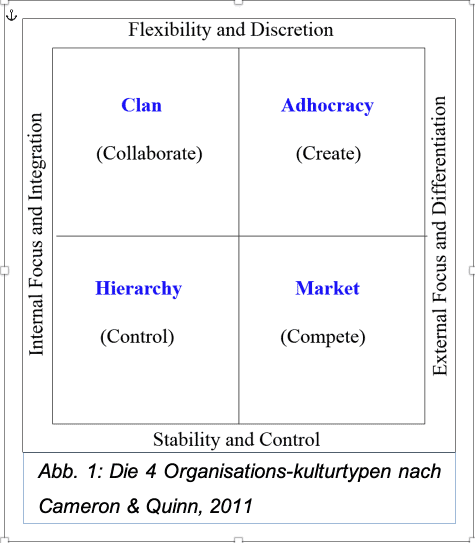

The concept of ambidexterity goes hand in hand with the competing value model by Cameron and Quinn (2011). The model proves that every organization can be in a tense relationship between different values without suffering any disadvantages as a result. On the contrary, this is normal (Cameron & Quinn, 2011). So there does not necessarily have to be a contradiction between ‘compliance’ on the one hand and ‘innovation’ on the other, or between an ‘adhocracy’ and a ‘hierarchy’ culture. Rather, it is important to maintain a positive tension between two cultures and values.

Quinn and Cameron (2011) distinguish four different organizational culture types in their competing values mModel, which are shown in Figure 1. In this approach, the hierarchy or ‘control’ culture type is about the values of efficiency, adherence to compliance, consistency, and uniformity. The achievement of goals should be rooted in control, efficiency, and capable processes. The management style in such an organizational culture is more transactional (Cameron & Quinn, 2011, Chapter 3).

Quinn and Cameron (2011) distinguish four different organizational culture types in their competing values mModel, which are shown in Figure 1. In this approach, the hierarchy or ‘control’ culture type is about the values of efficiency, adherence to compliance, consistency, and uniformity. The achievement of goals should be rooted in control, efficiency, and capable processes. The management style in such an organizational culture is more transactional (Cameron & Quinn, 2011, Chapter 3).

According to the competing values model, an innovation culture goes hand in hand with such values as innovative outputs, transformation, and agility. The organization follows a vision that, together with new resources, such as creative and technology-savvy employees, should ensure its effectiveness. This is an organizational culture of the adhocracy or ‘create’ type. For its part, the organizational structure should be flexible and able to implement transformations. The management style in such an organizational culture is more transactional (Cameron & Quinn, 2011, Chapter 3).

According to the competing values model, an innovation culture goes hand in hand with such values as innovative outputs, transformation, and agility. The organization follows a vision that, together with new resources, such as creative and technology-savvy employees, should ensure its effectiveness. This is an organizational culture of the adhocracy or ‘create’ type. For its part, the organizational structure should be flexible and able to implement transformations. The ideal leadership style in such an organizational culture is transformational.

2.3. 2.3. Without a new mindset, it is not going to be done

At this point, it is important for the organizations concerned to acknowledge this ‘as well as’ principle and to communicate it clearly. However, such an approach requires a rethinking of the existing culture, which is initially a task for top management. At the same time, this goes hand in hand with a new mindset: It is about granting individuals and teams a high degree of autonomy, trying out new paths, and integrating fault tolerance into their culture. On the way to this new mindset, clear and authentic communication on the part of managers plays a central role. ‘Authentic’ means that the leaders have rethought their own attitudes and are living by the principles they preach. Communication is only credible on this basis. The credibility of the executives is of central importance insofar as the introduction of autonomous teams and agile methods without authentic leadership and credible communication is doomed to failure. In this regard, Geramanis (2020) mentions, for instance, the introduction of Scrum as an agile project management tool although the daily stand-ups are not really open-minded due to the fear of sanctions. Such a scenario would be fatal as it would contradict a central principle of agile methods, which can be found not least in the Manifesto for Agile Software Development: ‘Set up projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need and trust them to get the job done,’ recommends the Manifesto. Leadership based on trust and appreciation promotes motivation and performance commitment among employees. It is important to reduce fear if necessary and to develop trust in a new culture. Regarding the agile methods, Geramanis (2020) says, ‘Without a corresponding anchoring in the organizational culture on the one hand and without the individual ability and willingness, on the other hand, to consistently get involved, they easily degenerate into an empty external form’ (Geramanis, 2020, p. 18).

In order to initiate a cultural change with the aim of combining agile and hierarchical structures into a successful unit, the top management of the organization must weigh up precise considerations. The question arises as to whether the two cultures need to be split into separate business units. Such a separation is recommended by Michael Tushman, professor at Harvard Business School. ‘Our basic notion is that the power of inertia in organizations is so strong that the only way to escape the inertia of a firm’s history is to separate the past from the future’ (Tushman, 2020, p. 121). Leading in connection with two different cultures is the greatest challenge for managers. This is also why separation makes sense. However, the top management must be able to live both cultures (i.e., to deal with ambiguity and insecurity).

2.4 Ambidexterity in practice

Regardless of the level at which the separation should take place, it is important for the managers concerned to learn what agile cultures are all about. Start-ups or traditionally run companies that have successfully implemented an agile transformation are an excellent source of inspiration for this. The electrical tool supplier Bosch, for instance, is a good example of organizations that have successfully set up a ‘dual organization.’ The successive approaches that the Bosch management tried out because the previous one failed (Rigby, Sutherland & Noble, 2018) are particularly interesting. Their transformation project was first started as a traditional-style project, that is, with an appointed project manager, formulated goals, a time schedule, and regular reports to the steering committee or management. Such an approach turned out to be unsuitable because it contradicts the agile principles. The project was canceled in this form, and a new approach was initiated. This time, the steering committee was converted into a ‘Working Committee.’ The discussions then became much more interactive. The team created and prioritized a list of necessary activities that was regularly updated and focused on removing company-wide barriers to greater agility. Geramanis (2020) supports this approach as he postulates: ‘At the structural level of the organization, above all, everything that makes self-organization in the team impossible must be left out.’ The department heads were included in the dialogue, and the process has now become continuous. The board members split into small teams and tested different approaches, some with a Product Owner and an Agile Master to tackle difficult problems or work on fundamental issues. In this way, Bosch managed the balancing act between agility and traditional structures. It is gratifying to note that the traditional part of the organization is now also committed to and applies agile values and methods (Rigby, Sutherland & Noble, 2018).

In addition to Bosch, there are other examples of successful implementation of self-organization theory (e.g., SAP). However, examples from other industries are not enough. Every organization has to find its own way. Indeed,

being inspired by others and then the long way to implement self-organization where it makes sense is recommended for all companies.

3. Conclusion

From both a scientific and a practical perspective, it is tempting that an organization does not have to intervene always and everywhere for it to work. The awareness that natural creative forces always accompany the formal processes of the work environment is something that every manager should internalize. Most organizations are able to apply the theory of self-organization. However, I need to emphasize that its application is not universal. In any case, its spirit is tempting, not only because it prioritizes agility and creativity and therefore favors a rapid adaptation of organizations to changed market conditions, but also because of its positive impact at the workplace. We humans often use specific terms that are in everyone’s mouth without sharing a common understanding about them. Nevertheless, every organization should be classified under the label ‘self-organization’, since formal and informal or natural forces are at work in parallel in every social organization. All actors and processes belong to the same system, whereby the system controls itself. On the other hand, this designation conveys the belief that social organizations or companies can function successfully without any fixed rules and management structures. However, not even an extreme form of self-organization like Holacracy [2] can work in this way. Even start-ups that begin with a high dose of self-organization must take care of management structures and formal processes once they grow. So sooner or later, many organizations have to master the tension between agility and control. On the way to agility in an ambidextrous self-organization approach, every organization has to find its way. In companies, board members and executives must be at the fore. Transformation projects that lead to self-organization with their promised agility should focus on people and their consciousness. It is not just about achieving economic goals but about the progress of the psychosocial system. Agility starts in the minds, i.e. in thinking and behavior. Transformations can hardly succeed if they are not initialized and completed with an agile mindset and by getting the support of employees at all levels. What should not happen is to believe that the path to agility is a purely rational one, or that the mere use of agile methods such as Scrum and Kanban

is sufficient.

[1] Trägheit[2] https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holokratieintermedio – 21.05.2021