Leadership and Management in China

Leadership – Communication – Culture

Since 30 years the country of the superlatives surprises the world with a breathtaking growth.

The Chinese leadership culture is influenced by the traditional philosophies of Daoism, Confucianism, and legalism. In addition, management and leadership models originating in Japan and Western countries have played an important role in China since the end of the Cultural Revolution. Although the mentioned philosophies were introduced in the pre-Christian period, they are still important as they continue to be powerful components not only of the Chinese value system but also of Japanese and other East Asian cultures.

Traditional values and conception of leadership.

Daoism

Daoism proposes a leadership style in which the superior intervenes as little as possible in the work of his subordinates. Laozi, the father of Daoism from the 6th century BC, said: “When the Master rules, people hardly notice that he exists. The next leader is a beloved leader. The next one is one who is feared. The worst is the one who is despised. If you do not trust people, you make them themselves untrustworthy. Master does not speak, h /she acts. When his/her work is done, people say, ‘It’s amazing, we’ve done it, all alone!’ ” (Chao-Chuan & Yeh-Ting, item 1203).

Contrary to Western thinking, which mainly follows an “either/or” pattern, Daoism is based on an “as well as” principle as a holistic way of thinking. The two models of thinking offer different perspectives and approaches to conflict management, decision-making, and leadership. A holistic human image is also the foundation of Abraham Maslow’s humanistic psychology. His works “Motivation and Personality” (1970) and “The Farther Reaches of Human Nature” (1971) are inspired by the Daoism concept (Chao-Chuan & Yeh-Ting, item 1251).

Confucianism

The human image underlying Confucianism is that man is basically a good being. However, each person is not considered as an individual but as part of a family and a community. The life of a human being was inherited by the ancestors and passed on to the next generation. This assumption is the basis of the East Asian family.

The doctrine of Confucius, on the other hand, has marked the Chinese leadership’s sense of morality and harmony. While it affirms a clear social hierarchy, executives deserve their status mainly through their moral qualities.

The ethical system of Confucianism is based on the values Triangle ren-yi-li (benevolence – righteousness – courtesy). This system encourages everyone to deal with respect as a basis for procedural justice. It prescribes that the decision-making power belongs to the individual who holds the higher position in the case of interacting parties. The necessity of a strong hierarchy is thus emphasized whereby obedience is owed to each superior by subordinates. The hierarchy here is to be understood in the broad sense, being defined not only by position but also by age and gender. Decision-makers are expected to have resources based on the rendao principle according to which they should treat acquaintances in a preferred way. This principle, which can be translated as the “way of humanity,” includes the following rules:

- Family members are preferably treated according to the “need rule.”

- Relationships within the guanxi (relationship network) should be treated according to the renqing (affective) principle.

In this case, we can observe the different conceptions of ethics in the West as opposed to East Asia. While in the West, favoring friends and family is regarded as bribery, it is rather seen as good behavior in China.

Alexander Thomas, the German psychologist and author of Cultural Standards, uses a practice case that reveals the abovementioned divergent values between Chinese and Germans as follows:

The German representative of a German company in China and his wife are friends with a Chinese couple. The Chinese, who once gave the German a little help as an interpreter, one day asked the representative to give her son a job in the German company. As the German man was not willing to do this because, in his perception, this would be within the limits of bribery, the Chinese couple broke off their relationship with the German couple (Thomas, 2008, item 1387).

Based on the above-mentioned philosophy, this can be explained as follows: while the Germans feel abused by the Chinese couple’s expectation, the Chinese pair interpreted the negative attitude of the German representative as a violation of the Chinese rules of friendship (Renqing), the more so because the Germans are, compared to the Chinese, considered rich and powerful, and the Renqing principle demands the greatest number of possible mutual favors within the network of relationships (guanxi).

Confucianism sets different standards for the “common people” and for scholars. For ordinary people, it is sufficient that they live according to an ethical system after Ren-Yi Li. Their social system is oriented to the family; their behavior is to be controlled by courtesy (Li), and the decision-maker is the family head.

The will to lifelong learning is an attitude praised in Chinese philosophies. But it is more expected of scholars than by ordinary people. Scholars should apply the principles of Rendao, i.e., disseminate their knowledge to the widest possible circle within society. Thus, they are guided by the value of collectivism (Chao-Chuan Chen & Yeh-Ting Lee, 2008, Pos.1576).

Legalism

Legalism is based more on law than on moral values. Its basic assumption is that human behavior is primarily controlled by a relentless pursuit of self-interest, not by moral values. This position corresponds to that of the sociologist Max Weber, the father of German sociology (Chao-Chuan & Yeh-Ting, pos. 1704).

This leadership theory of Hanfei, a philosopher and founder of legalism, who lived in the 3rd century BC, is based on three pillars:

- Shih (power)

- Fa (law) and

- Shu

(art of manipulation, which is applied for control of subordinates).

The interactions between executives and subordinates are expressed in Chinese legalism as follows:

“The boss never expresses any malicious anger, and the subordinate has no hidden dissatisfaction in the mind” so that “superiors and subordinates can interact with each other smoothly.” This is a central aspect of legalism (Chao-Chuan Chen & Yeh-Ting, item 1452).

Hanfei’s concept covers not only modern leadership aspects such as the principle according to which the subordinates have to propose appropriate solutions in order to achieve goals, but sets a foundation for project and conflict management. This principle was applied when the state was confronted with complex problems that arose beyond the daily routine tasks. Hanfei has provided for this case the following Shu principle: the focus is on agreed or ordered goals of the subordinate. Communication is of great value in this process. As a utilitarian, Hanfei was convinced that the first task of a leader was to examine the effectiveness of the subordinate’s efforts to achieve the defined goals. In the performance appraisal, therefore, the superior controls the congruence of the words and deeds of his subordinate and critically questions the effectiveness of his actions (Chao-Chuan Chen & Yeh-Ting Lee, item 1502).

This style of management is reminiscent of Management by Objectives, by setting goals for the subordinate and periodically discussing their level of achievement between supervisors and subordinates. The aspects examined by the managerial leadership suggest a coaching relationship.

During the Han Dynasty, Chinese society lived according to the dual principle of Confucianism in private and legalism in the public sphere. After the end of this dynasty, a mixture of both philosophies was applied.

In contrast to Confucianism, a legalist leader distributes rewards and penalties to subordinates in relation to their contributions to organizational objectives. According to Chao-Chuan Chen and Yeh-Ting Lee (2008), this style of leadership contains both an individualistic aspect (by rewarding and punishing individual achievements), as well as a collectivist one (since the highest priority is given to organizational or national goals).

Comparison of Confucianism and Legalism and Its Meaning in Chinese Society Today

The principles of Confucianism and legalism create a dilemma for many Chinese leaders. Their influence is clearly reflected in the management of companies and political organizations.

| Confucianism | Confucianism | Legalism | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethics for common people | Ethics for scholars | ||

| Value-orientation | Familism | Collectivism | Individualism and collectivism |

| Social norm | Decency (Li) | Benevolence (Ren) | Laws (Fa) |

| Sharing rule | Need | Equal rights | Justice |

| Critera for sharing | Blood relationship | Membership | Contributions |

| Decision maker | Family head | Elite | Ruler |

Table 2. Comparison of Confucianism and Legalism in Five Dimensions

The slogan for the communist cultural revolution between 1966 and 1976 was, “Denounce Confucianism and promote legalism.””People should follow the principles of Marxism” (Chao-Chuan & Jeh Ting, 2008). The influence of Marxism on the two philosophies, however, remains modest.

What Confucianism and legalism have in common is that both concepts are collectivist and have supported a paternalistic style of leadership until today. They are also characterized by a very low delegation of power to employees, even in Taiwanese firms. (Chao-Chuan Chen & Yeh-Ting Lee, pos. 1660-1664).

The Art of War by Sunzi

Historians do not know exactly when the Chinese General Sunzi lived. It is thought that he was a contemporary of Confucius. Interestingly, his “Art of War” is the first treatise on war strategy in history. This strategy is governed by a leadership and management theory that inspires today’s CEOs in their leading roles.

The concept includes strategic and leadership attributes:

- Strategic leadership

- Situation

- Subordinates

While the strategic perspective focuses on the opponent, the leadership perspective focuses on the leader, his inferiors, and their interaction with the environment. Sunzi’s concept of leadership applies the humanist principles of Confucianism and Daoism, i.e., benevolence, the authority of the superior, paternalism, and holistic thinking. One aspect that can be inspiring in the analysis of modern leadership styles is one of situationism. According to this concept, the morality and cohesion of the subordinates depend less on their intrinsic properties than on their particular situations.

Figure 1: Sunzi’s model of Strategic Situationism (Chao-Chuan & Yeh-Ting, 2008)

Interestingly, Walter Mischel, an American psychologist, developed an intense debate about the same theory in 1968. In his book Personality and Assessment, Mischel emphasizes that human behavior depends largely on the requirements of a situation. The view that individuals behave consistently in different situations because of their personality is simply a myth. “Although it is evident that persons are the source from which from which human responses are evoked, it is situational stimuli that evoke them, and it is changes in conditions that alter them” (Mischel, 1968, p 295-296).

This theory is important to our study in that it is not only the objectives and the employees that are to be observed, but the environment and its development are to be observed, as well. In performance assessment talks, affected employees frequently mention the change in the environment as a cause of not achieving their goals. Therefore, it is also advisable to consider the environment and its changes on a regular basis and, where appropriate, adapt to the targets set.

Modern practice of leadership in mainland China.

A mix of traditional and western concepts

When you look at the current state of leadership in China, you are confronted with a mixture of different streams. What can be astonishing is how sustainably and deeply noticeable the traces of the 2,500-year-old philosophies are in today’s society. Even if the influence of the West has lasted for almost 40 years, through numerous companies and joint ventures, and many Chinese managers have completed MBA courses in the US and other Western countries, a “We” society with a paternalistic leadership style remains predominant.

It is essential to distinguish between public and private organizations. In the private sector, the influence of Western and Japanese management models is stronger than in the state. Government organizations remain focused on altruism in the context of a stronger collectivism, while the private sector is more concerned about efficiency. In the government sector, a more sophisticated form of performance assessment is applied. The process begins with a self-assessment of the employee himself, followed by an assessment by his team colleagues at a joint meeting. Then, the performance assessment form is signed by the department head and handed over to the personnel department (Cooke, 2012, item 1747).

Western management theories were introduced in China mainly through MBA courses. Business schools in the country have mostly used teaching material from North America in original or translated form. In business administration courses, many managers prefer professors who master both Western and Chinese management theories (Chao-Chuan & Yeh-Ting, 2008, item 3244).

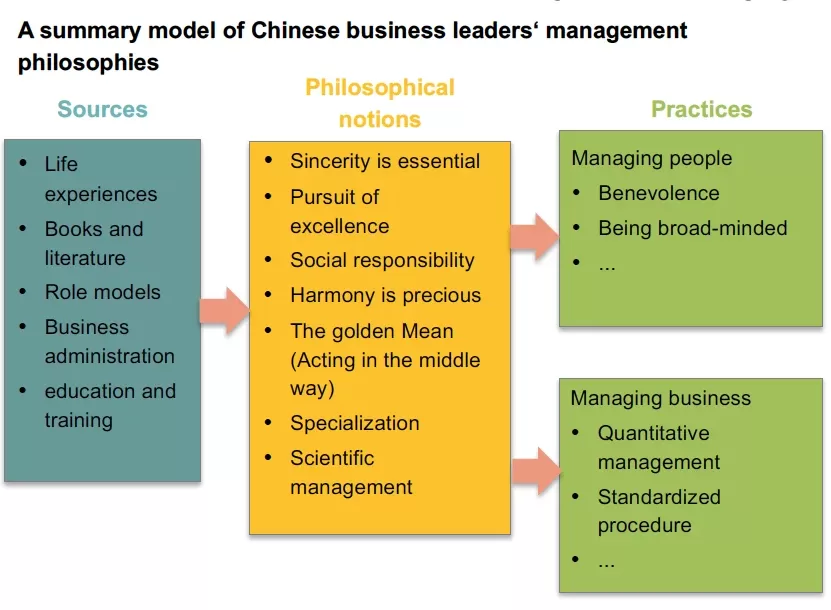

The mix of traditional Chinese values and Western theories is best seen in the results of a survey of 35 CEOs of companies with a number of employees between 110 and 5,000. Nine of these were held by state companies, while the remaining 26 managing directors were active for private companies. In interviews of between 60 and 150 minutes, they were asked to describe their management philosophy. They then had to reflect the sources of their philosophy as well as the derived values and concepts. The consolidated results of this reflection are shown in Figure 3 below. One can note that the values of sincerity, the golden mean, social responsibility, harmony and benevolence propagated by the traditional philosophies are always omnipresent.

A mix of traditional and western concepts

When you look at the current state of leadership in China, you are confronted with a mixture of different streams. What can be astonishing is how sustainably and deeply noticeable the traces of the 2,500-year-old philosophies are in today’s society. Even if the influence of the West has lasted for almost 40 years, through numerous companies and joint ventures, and many Chinese managers have completed MBA courses in the US and other Western countries, a “We” society with a paternalistic leadership style remains predominant.

It is essential to distinguish between public and private organizations. In the private sector, the influence of Western and Japanese management models is stronger than in the state. Government organizations remain focused on altruism in the context of a stronger collectivism, while the private sector is more concerned about efficiency. In the government sector, a more sophisticated form of performance assessment is applied. The process begins with a self-assessment of the employee himself, followed by an assessment by his team colleagues at a joint meeting. Then, the performance assessment form is signed by the department head and handed over to the personnel department (Cooke, 2012, item 1747).

Picture 2: Phlisophy of Chinese Leadership Concepts

Western management theories were introduced in China mainly through MBA courses. Business schools in the country have mostly used teaching material from North America in original or translated form. In business administration courses, many managers prefer professors who master both Western and Chinese management theories (Chao-Chuan & Yeh-Ting, 2008, item 3244).

The mix of traditional Chinese values and Western theories is best seen in the results of a survey of 35 CEOs of companies with a number of employees between 110 and 5,000. Nine of these were held by state companies, while the remaining 26 managing directors were active for private companies. In interviews of between 60 and 150 minutes, they were asked to describe their management philosophy. They then had to reflect the sources of their philosophy as well as the derived values and concepts. The consolidated results of this reflection are shown in Figure 3 below. One can note that the values of sincerity, the golden mean, social responsibility, harmony and benevolence propagated by the traditional philosophies are always omnipresent.

Management by Objectives in China

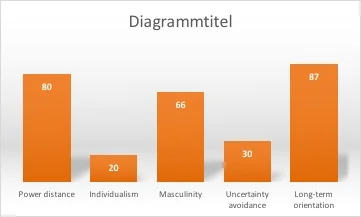

The dimension of Chinese culture, which, according to Hofstede, does not match the concept of the MbO, is the very high power distance. In this context, a high power gap index means that communication between supervisors and employees does not take place on the same level but is characterized by paternalism and obedience, respectively. It is likely that employees are generally expecting instructions from their superiors and are less likely to represent their own, thought-out opinion. If they are dealing with a supervisor who acts exclusively with a participatory management style, it is almost inevitable that the communication becomes extremely frustrating for both.

Picture 3: Cultural dimensions of China

The combination of a high power gap and deep individualism makes the leadership of supervisors from Western countries extremely complex, so much more important than the seniority and the age of the actors in Chinese society. There is also an important point which makes the communication much more difficult: Direct criticism against Chinese employees is very problematic. This goes against the principle of harmony and avoiding facial loss. Chinese leaders therefore have a tendency not to reproach, but to treat all employees on an equal footing.

The masculinity index is relatively high at 66, and the uncertainty prevention at 30 is relatively low. Unlike the Power Distances Index, these two values support the MbO process. As their languages reflect this, the Chinese can handle the ambiguity well.

Conclusions for the application of the MbO in the Chinese Leadership Concepts

Given the very high power gap, expectations of executives from Western countries would be disappointed in the autonomous operation of Chinese employees in many cases. In this respect, it would be unfair to assess Chinese workers on the basis of Western cultural standards. With the provison that conclusions drawn from cultural dimensions are always to be enjoyed with caution on an individual level, goal agreements should be more oriented around the team spirit of the respective employee rather than on individual achievements. A mixture of collective and individual objectives would also make sense.

As far as performance assessment is concerned, executives should avoid accusations when possible. Communication with employees who experience loss of face again and again will probably be very difficult. Particular attention should be paid to a balanced distribution of rewards. Again, depending on the context, collective rewards might be more individual than individual ones.

Comparison of Singapore, Taiwan and Hongkong with mainland China

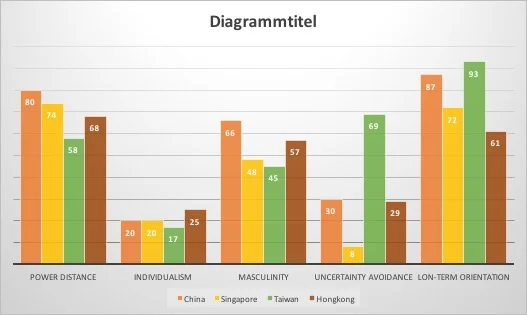

The cultural dimension indices of Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong show very similar values to those of mainland China with regard to individualism. Thus, the Chinese community remains collectivistic, with Hong Kong showing more individualism. Nevertheless, in view of the past of the former British colony, its position as a worldwide financial center, and the presence of many nationals from the USA, Europe, and Australia, an individualism index of 25 is surprisingly low.

Picture 4: Cultural dimensions of China, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong (Hofstede Center)

Special features of Singapore

The Power Distances Index of Singapore is fairly close to the value of mainland-

China. The Confucian background with a strong social hierarchy as in China based on position in society, seniority, age, and sex explain the high PDI. Remarkable is the very deep uncertainty avoidance. This can be linked to the high diversity of the population, as well as to social stability, an extremely strong economy, a high standard of living and a strong trust in one’s own government. This feature means that people from Singapore have a high ambiguity tolerance. This makes communication within an organization, and especially in a MbO process, easier. In principle, however, the same basic rules as for China should be observed.