Leadership and Management in Japan

Cross-cultural Leadership and Management in Japan.

Ensure the success of your exchanges with Japan thanks to our cross-cultural courses and workshops. For top leadership, communication and customer relations!

In fact, these concepts have been in use around the world for several decades, regardless of local cultures. Japan is no exception. There, too, most organizations use models such as Management by Objectives (MbO). Nevertheless, the Japanese have very different expectations and behavior patterns than people from the western world. However, some European executives may wonder what adequate leadership and communication with Japanese employees should look like. Japanese culture provides the answer.

Traditional values and notions of leadership.

influence of religions

Cult and belief characterize Japanese society and its values. Japan's oldest cult is Shintoism. Although Buddhism from China via Korea did not reach Japan until the 6th century, both faiths coexist syncretically. “Most Japanese marry according to the Shinto tradition and have their funeral mass read by a Buddhist priest. The Shinto-Buddhist syncretism not only arose spontaneously from the way of life in the communities, it was also deliberately cultivated” (Coulmas, 2014).

However, even in this early period, the Japanese showed that they could skillfully adopt ideas from abroad and adapt them to their circumstances. Thus they developed Mahāyāna Buddhism as a Japanese form of Buddhism.

Influence of Confucianism

Along with Buddhism came Confucianism from China. The two philosophies shaped Japanese culture and, from the 7th century onwards, the constitution of Japan, the administration of the state and the behavior of the dignitaries and the morals of the common people very early on. "Sincerity and incorruptibility are commandments inspired by Confucianism, while selflessness and overcoming human urges reflect Buddhist principles" (Coulmas, 2014).

Although Confucianism was denied in various periods of Japanese history, its ethos still shapes the behavior of the Japanese people today, even if they are no longer referred to under the name of Confucius. They are to be regarded as universal values, so to speak.

The values prominent in Japanese culture are similar to those in China. The family is the most important unit in society, the individual humbles himself and places himself in the background of a community, which he serves benevolently and dutifully. Respect for age and authority, frugality and sincerity are virtues underlying the behavioral patterns of Japanese people. Great importance is attached to interpersonal relationships. Harmony and saving face are guiding principles in the design of communication.

Communication.

As in every culture, leadership and management in Japan have their own culture-specific behavior and communication patterns:

handling information

The different perspectives and attitudes between Western and Japanese cultures are concretely illustrated in the way information is perceived and used: Americans and Europeans see information as a means of power. Therefore, they may tend to withhold information from colleagues in order to distinguish themselves. Not so the Japanese, who provide information at all times in the service of the team and organization (Whitehill, 1991). That sounds plausible, since like their employers, Japanese employees have a long-term perspective on their career and do not focus on short-term success. Lifetime employment, widely practiced by Japanese companies, takes some of the pressure off employees' shoulders and favors a collaborative attitude.

Dealing with the silence

Like the Chinese, but unlike Western Europeans and Americans, the Japanese are very good at using silence in joint meetings. Switching on quiet moments during work sessions is not uncommon, with the silence serving not for relaxation per se but for individual reflection. People from Western countries who feel the need for an uninterrupted flow of discussion in encounters are well advised to take this aspect into account when communicating with East Asians. "Anyone who has endured long periods of silence in a team or in a meeting with Japanese and has not fallen into the Western trap of "filling in the gaps" has arrived in Japan" (Haller, Nagele, 2014).

Written, oral and non-verbal communication

The aversion to legally regulated agreements and lawyers finds its counterpart in written communication, which the Japanese consider mandatory mainly for annual reports, reports to the government organs or for complex content. Written communication strikes the Japanese as cold, impersonal and, most importantly, deficient in terms of a shared understanding of the content (Whitehill, 1991). The testimony of a researcher from the Mitsubishi Research Institute may confirm the aversion to the written word in business relationships:

"Many Japanese businessmen won't take any notes during a meeting. Topmanagers especially are supposed to be good listeners, with no memo pads or pens“ (Whitehill, 1991).

In oral communication one always recognizes the importance of the relationship and the desire for harmony and respect. Non-verbal communication is very important when interacting with Japanese people.

.

Japanese have developed a subtle way of communicating their expectations and feelings without words. The process that drives this mutual feeling is called haragei (in English "gut language") and is supported by body language (Whitehill, 1991).

decision-making processes

In Japanese companies, decisions are primarily initiated by middle management according to a bottom-up process called "Ringi", with top management having the final say. The “Ringi” stipulates that the manager hands over a folder to his subordinates that contains the details of the problem to be solved. Managers are asked to present their point of view. Then they in turn perform the same action with their subordinates.

This ensures that all relevant opinions have been collected before the final decision is made. At the end, the folder returns to the initiator.

Such a process would be unimaginable for managers from Western countries because it delays decisions beyond local standards. Its great advantage, however, is that all affected employees stand behind the respective decision because they were involved in it themselves. The time invested before the decision is made pays off later, when there is no longer a need to inform, educate and, if necessary, convince the employees concerned. On the other hand, decisions that Western managements make on their own and are merely communicated to the bottom often trigger resistance and disagreements because the employees lack the intellectual basis that led to the decisions.

Leadership and Management Japan - Leadership style.

values and behavior patterns

Japanese culture and values are reflected in the following behavior patterns:

- Loyalty to superiors, unconditional devotion to one's own family

- Constant striving for further education, diplomas and self-development.

- Avoidance of shame and loss of face deeply shapes the behavior of the Japanese. This aspiration applies not only to them as individuals, but to their family, their team, their employer and even Japan. You feel a loss of face in some situations that people from western countries approach with composure. The different perspectives are potential triggers of so-called critical incidents.

- The team is more important than the individual. Unlike Individualistic cultures like America, Japanese would not withhold information from their peers for sole benefit. Japanese always strive for harmony in the organization. Ironically, they say that they compete after all. The best way to compete is precisely to put oneself at the service of the team, since team spirit is one of the most important criteria for evaluating their performance and career

- Gratitude: The (Confucian) principle of benevolence accompanies people in their relationships. The gratitude for a service rendered by the supervisor is immense. Japanese say that such a heavy debt can never be repaid. The person concerned will feel obligated to their superior for the rest of their life. This concept is called on in Japanese. For smaller debts, there is the Giri concept, which allows 1:1 compensation.

- Empathy: Although slightly different from on or giri, the Japanese know ninjo (human feelings) as a duty. Unlike Western cultures, where "I'm sorry" or "I know how you feel" is said, ninjo is about feeling empathy without saying it. (Whitehill, 1991).

- Trust versus legal: while a single major American firm can employ hundreds of salaried lawyers, Japanese firms don't feel the same need. They rely on relationships and trust rather than legal processes (Whitehill, 1991).

- Conflict Avoidance with Honne and Tatemae: Honne is what a Japanese really feels and Tatemae is the facade behind which his feelings are hidden. This duality could be viewed as hypocritical in other cultures. The Japanese use it to preserve harmony. This is particularly important in the workplace, where behavior is always characterized by tatemae. Downloading emotions then takes place in the evening in the relaxed atmosphere of a bar with misuari (whiskey with water) and possibly karaoke.

Should a conflict arise between a Japanese manager and a German representative, for which there is a lot of potential in reality due to the direct communication style of the Germans, the situation and the relationship can only be saved with a special ritual called nemawashi (planting a little tree).

Importance of the employees in the organization

In both Western countries and Japan, managers emphasize the importance of human resource management to the organization. But there is one essential difference between these cultures: the Japanese apply this principle very thoroughly. As one example among many others, Keizaburo Yamada, Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors of Mitsubishi Corporation (MC), once said:

“MC is a community of 10,000 people who share a common destiny. The top must try to understand the thinking of the base and vice versa”. Considering that employees are one of the fixed assets of the Japanese company, it is understandable that a great deal of attention is paid to their well-being (Arthur M. Whitehill, 1991).

“Workers in Japanese workplaces belong to a group, and it is groups, not individual employees, who are given tasks” (Coulmas, 2014). Whitehill expresses the same principle by quoting M.Y. Yoshino, Prof. and Director of Research at Harvard Business School: “The basic unit in the organization is a collectivity, not an individual. In read one of the fundamental differences between American and Japanese management” (Whitehall, 1991).

When it comes to hiring staff, there is a fundamental difference to the West.

Japanese companies hire candidates for the company, not for a specific job. Employees are likely to join the company for the rest of their lives. Of course, such an arrangement results in a very different relationship between employers and employees than, for example, in America, where employees are fundamentally regarded as readily exchangeable resources.

Functions are vaguely described on an individual level, since it is not the individual employees who are given orders, but the team. The transitions are also fluid at the team level, so that cooperation between the teams is promoted instead of "garden thinking". However, the question arises as to how the individual in Japanese organizations ensures his or her advancement. At this point there is again a fundamental difference to Western cultures. While people from Western countries see a conflict between their own ambition and cooperation with others, the Japanese distinguish themselves through teamwork, as this ability is highly valued.

This principle is confirmed by Whitehil:

“A good point is made that individuals in the Japanese Kaisha (company) do compete. But such interpersonal competition is aimed at gaining the more desirable position assignments and special considerations in long-term career development rather than at getting an immediate promotion or salary increase. To a Japanese, the dichotomy seen by American workers between competition and cooperation is a false one. The Japanese way to compete is through teamwork” (Arthur M. Whitehill, 1991).

Japanese Perspective on the MbO.

Preferences of Japanese employees

The content of the table below is the result of a survey targeting Japanese and US employees in 1981. The questions to be answered aimed to determine how the performance appraisal process should ideally be designed for these employees in order to maximize their satisfaction. Although this survey is old, it shows attitudes from both sides that have changed little to this day.

| Preferences | Japan | USA |

|---|---|---|

| Assess performance and inform each employee of their weaknesses and strengths. | 30% | 70% |

| Evaluate employees, compare them with each other and inform them about their strengths. | 22% | 11% |

| Assess and compare, but keep the results secret. | 31% | 4% |

| Avoid judgments and comparisons of individual performance as much as possible. | 17% | 15% |

Table 1: US-Japan Employee Preferences (Whitehill, 1991)

These results underline the inhibitions of Japanese employees with regard to a transparent performance appraisal process. The Japanese, in particular, have a hard time revealing and discussing their weaknesses because it could probably cause a loss of face. Only 30% of those questioned would like to be informed about their strengths as well as their weaknesses.

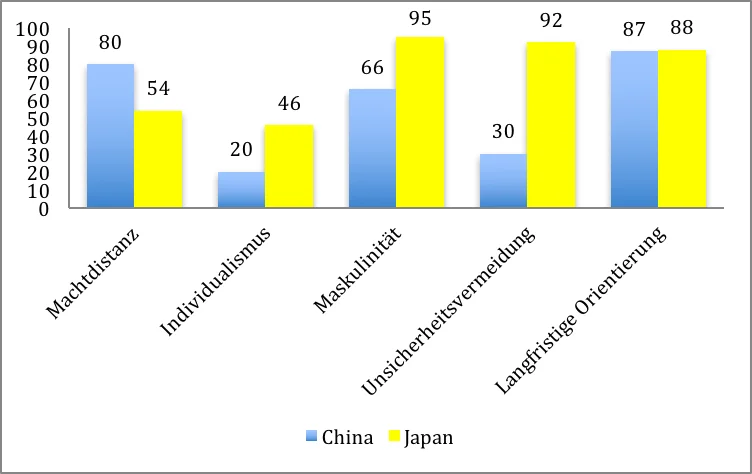

Comparison with China based on the cultural dimensions

In terms of significantly lower power distance and higher masculinity, Japanese employees appear to be better armed than the Chinese for the performance appraisal process. However, uncertainty avoidance is immensely higher than among the Chinese.

A study conducted in 1999 by Osaka City University shows that MbO has been used as a performance appraisal system by numerous Japanese companies since the 1960s. In the 1970s, the popularity of the instrument received another boost: “As a result of high economic growth their intense commitment to the company seemed to decrease. Japanese companies had to find an effective way to improve employee's ability and motivation in their work. Again MbO became popular among such companies. This time, experience with MbO as a quota system led them to emphasize the participation of employees. They were encouraged to set their goals, accomplish them, and check the accomplishment by themselves.

.

Through participation employees were expected to improve their ability and work motivation. MbO adopted in this way often lacked a chain of objectives from the top to the lowest levels. The objectives were set freely by subordinates and superiors were encouraged to accept them wherever possible” (Akiko Okuno, 1999).

Recommendations for the leadership of Japanese associates

To be successful, Western executives should understand exactly how leadership and management works in Japan. When interacting with Japanese employees, it is advisable, as in the case of China, to show leadership that is as appreciative and impartial as possible. Japanese employees tend to work enormous hours, identify strongly with their employer, are honest, loyal and expect a benevolent attitude from their employer. Although their individualism is stronger than that of the Chinese, the Japanese are excellent team players. However, this does not mean that Japanese employees can be seamlessly integrated into every team. The following constellations may explain this:

- Compared to Europeans, the attitudes and behavior patterns, which are far apart, endanger communication and harmony in the team

- Compared to Europeans, the Japanese are considered collectivists. In the eyes of the Chinese, however, they are individualists. Not only the individualism but also the masculinity and the avoidance of uncertainty show enormous differences between Chinese and Japanese. These discrepancies are likely to cause some problems in communication between the two cultures.